The best defence is a good offense

There is no clear consensus on the definition of hybrid warfare. The European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats (Hybrid CoE) defines it as ‘actions conducted by state or non-state actors, whose goal is to undermine or harm a target by combining overt and covert military and non-military means.

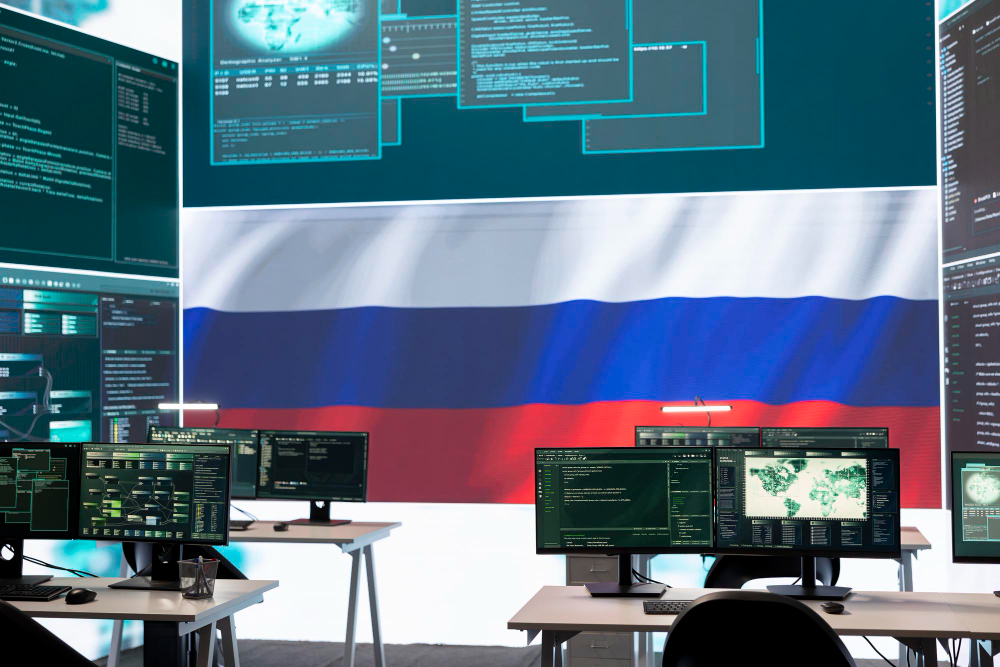

As part of their threat image as presented by The Dutch National Coordinator for Counterterrorism and Security (NCTV) describes that Russia has conducted espionage operations aimed at Dutch underwater infrastructure, such as internet cables, gas pipes, coastal wind energy plants but also drinking water and energy installations, possibly aimed for future sabotage attempts. Russian hack attempts have also been directed at the Organization for the ban of chemical weapons (OPCW). Additionally, concerns exist regarding Russian influence on Dutch political senior leadership, even though this is difficult to prove.

Such hybrid activities usually aim to target opponents by conducting operations under a ‘sub-threshold battlefield – often referred to as the ‘grey zone’, where states and non-state actors compete in a hostile manner using a variety of tactics but below the threshold of war’. Perpetrators usually try to avoid attribution or retribution. Simply put, an offensive hybrid action cannot be attributed and linked to a specific actor, or at the very least leave enough room for ambiguity on the target and its population. Retribution is the punishment which can be inflicted as vengeance in response to a hybrid attack. This is where Europe – including the Netherlands – goes woefully wrong with Russia. There is little, or no retribution to speak of, other then on occasion expelling Russian spies or diplomats.

About the Author

Erik Stijnman is an Army Lieutenant Colonel in active Dutch Service and has been seconded to Clingendael as Senior Research Fellow with Clingendael’s Security Unit.