A key trend in European politics since the 1990s has been the delegation of important policymaking responsibilities to unelected decision-makers such as independent agencies and supranational actors. Takuya Onoda writes that while this has frequently been viewed as a process of depoliticisation, the use of unelected bodies can paradoxically increase the political contestation of policy decisions.

Is government too political? When Alan Blinder, former vice chairman of the United States Federal Reserve, asked this question in a 1997 Foreign Affairs essay, he certainly captured the prevailing mood of the time. The 1990s ushered in an era of state transformation, as delegated policymaking bodies – such as independent regulatory agencies and central banks and supranational organisations like the European Union (EU) – spread across the world.

Their proponents, like Blinder and the political scientist Giandomenico Majone, contended that delegating powers to unelected experts would contribute to policy stability and effectiveness. Their critics argued that the proliferation of such unelected bodies would result in what Peter Mair termed the ‘hollowing out of democracy’ and would shield politicians from responsibility and public scrutiny.

Both the proponents and critics, however, had one thing in common: they viewed the creation of unelected bodies as a shift towards ‘depoliticisation’, a process in which issues move beyond the scope of governmental and public arenas, removing the potential for debates, choices, and actions associated with politics.

Yet, growing attention given to political struggles after the creation of unelected bodies calls this assumption into question. What recent scholarship has begun to reveal is that regulatory institutions, ranging from regulators to central banks to the EU’s institutions, have increasingly become the focus of political contestation. This raises the question of what the mechanisms are for driving this apparent (re)politicisation of supposedly depoliticised institutions.

Politicisation from within

Drawing on a study of drug rationing policies, I highlight the drivers of the politicisation emerging from within – that is to say, the forces generated by the regulatory institutions themselves. I argue that a key to understanding the policy trajectories after the creation of a regulator lies in the extent to which decision-making powers are transferred from elected politicians to the regulator.

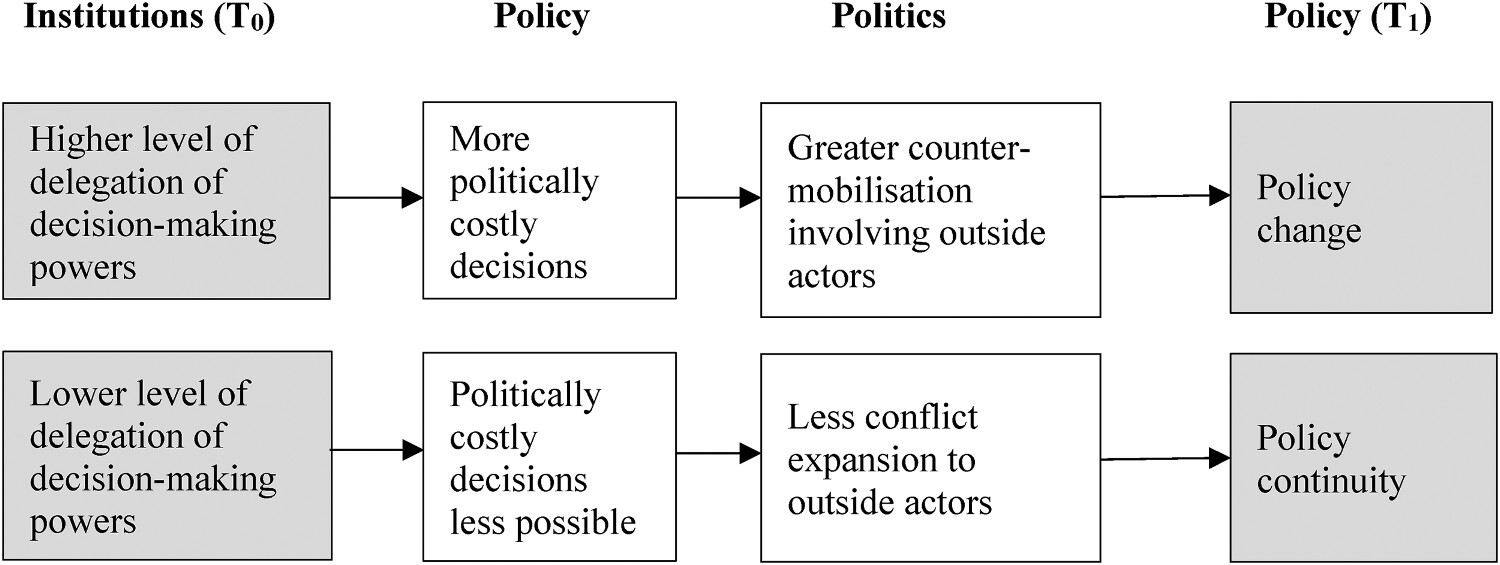

Why is this so? The degree of delegation matters for the subsequent political struggles because it shapes the ability of the decision-maker to impose losses on society. This is summarised in Figure 1. This shows that highly-delegated settings that take decision-making powers away from politicians enable policy decisions that are likely to prove politically costly.

Figure 1: Political dynamics and policy development after the creation of a regulator

But such decisions, once made, are likely to generate greater counter-mobilisation in the public arena, undermining policy stability over time. By contrast, in a less delegated setting where elected politicians hold their decision-making powers in their hands, they can prevent unpopular choices from being taken. By blocking the opportunity to expand conflicts, the actions of such politicians contribute to policy continuity.

Of course, things don’t always get politicised even in a highly-delegated setting. Each step of the overall mechanism is expected to occur only under certain conditions. Hence, a regulator with decision-making powers can produce politically costly decisions only when it can act autonomously. Moreover, a loss-imposing decision is more likely to get politicised when the concentrated loss is made visible to the public. This may occur through scandals or crises – events that quickly draw public attention.

Rationing drugs in England and France

Drug rationing policies – or the restriction of funding of drugs by healthcare systems – illuminate these dynamics. Here, the need for independent regulation has been at its greatest. Technological advances and demographic change have presented governments with often-contradictory pressures around funding drugs, including controlling cost, ensuring citizens’ access, and rewarding innovating industries.

Since the 1990s, many European governments have created regulatory agencies tasked with assessing the clinical- and/or cost-effectiveness of medical technologies, with the hope that they would base rationing more on evidence and expertise and would achieve a rational resource allocation. Yet, rationing (or ‘healthcare priority-setting’, as some would prefer to call it) is hardly a technical choice but rather a political act; a decision to exclude drugs from the public healthcare system generates losses among sections of society.

A comparison between England and France illustrates how the varying ability to create such losses, anchored by the different degrees of delegation of decision-making powers, has shaped policy trajectories. The two countries share several national and sectoral conditions, including demographic trends, a strong executive, a majoritarian electoral system, and the strategic importance of the pharmaceutical industry. Both set up regulatory agencies between the late 1990s and early 2000s. But the trajectories of the two countries diverged thereafter.

In England, with the creation of the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE, now National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) in 1999, the decision-making powers were delegated to the agency. Once NICE issued its Technology Appraisal guidance – recommendation on whether a drug should be funded by the National Health Service (NHS) – it became the final decision for the NHS. This arrangement enabled NICE to produce ‘tough’ choices, where its Technology Appraisal Committee judged a drug as lacking ‘value for money’ for the NHS, without ministerial interference.

Yet, such choices, once made, were subject to intense counter-mobilisation by drug companies and patient groups. Their publicity campaign, often covered extensively by the media, broadened their base of mobilisation by drawing public attention to the negative impact of decisions. The heightened public attention, in turn, resulted in the introduction of measures to improve the availability of cancer drugs – an area where the controversy was at its greatest.

Perhaps the clearest example of such measures was the Cancer Drugs Fund. Pledged by Conservative leader David Cameron for the 2010 general election, the Fund provided a ring-fenced budget within the NHS which covered the cost of cancer drugs rejected by NICE. Having spent £968 million by March 2015, the Fund effectively overrode the NICE guidance and prioritised cancer drugs over other treatments and services.

France followed a different path. Both before and after the creation of the independent regulatory agency Haute Autorité de Santé (HAS) in 2004, it was the health minister, after HAS issuing its opinion, who made the final decision on whether a drug would be included in the reimbursement list.

With decision-making powers in their hands, ministers prevented unpopular choices from being made. Throughout the 2000s, both Socialist and centre-right Gaullist ministers avoided de-reimbursing drugs that HAS judged insufficient in clinical benefit. As the Gaullist health minister Xavier Bertrand put it, by refusing to follow the HAS opinion, his role was to ‘take into account the social reality’, as opposed to HAS’s ‘scientific assessment’.

Ironically, one of the drugs the experts judged insufficient in clinical benefit was Mediator, a diabetes drug that was alleged to have caused from 500 to 2000 deaths before being withdrawn from the market in 2009. Ministers likewise distanced themselves from reforms that might make unpopular policies possible, such as the use of economic evaluation in the reimbursement decision. Despite the arrival of new, expensive drugs, few measures were thus introduced to change the occurrence of rationing decisions.

The impossibility of removing the political

These findings are important, as they challenge the conventional view that insulating policymaking from politics through delegation is crucial for policy stability. Rather, it can actually result in instability by becoming a source of politicisation itself. Of course, we need to be cautious about the generalisability of the findings. Nevertheless, they highlight the difficulties that attempts to remove politics from decision-making face. Government might ultimately prove to be no less political after the creation of unelected bodies.

About the Author

Takuya Onoda

Takuya Onoda is a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellow in the Centre for European Studies and Comparative Politics at Sciences Po, Paris, France.