The current US administration plans to protect the entire territory of the United States against any potential air or missile attack. The focus is on deploying large satellite constellations capable of detecting and intercepting long-range missiles shortly after launch. Even if only a fraction of this ambitious plan is likely to be implemented, it is probable that there will be progress in missile defense during the coming years. For Germany and Europe, the risks and potential benefits – especially with regard to space-based US missile defense – are difficult to assess at the current time. However, Europe can maintain the largest possible room for maneuver by avoiding an open confrontation over Trump’s plans.

In January 2025, President Trump announced the “Golden Dome” initiative, a US missile defense program based on an idea that harks back to a Cold War project. The new initiative was first mentioned in the form of a promise during Trump’s first term and was taken up again in the 2024 presidential campaign.

The idea is simple, the ambition extraordinary: Trump wants to protect all US territory against any type of air attack – by aircraft, drone, or missile – regardless of the country of origin. That means possible attacks by Russia or China are included in this calculus. Admittedly, it is difficult to distinguish new initiatives from existing programs. However, the administration has already taken a series of legal, administrative, and financial measures intended to contribute to the establishment of Golden Dome. According to the White House, the project will cost US$175 billion and be completed by the end of Trump’s second term (in 2029).

Although much remains unclear, it is certain that the system will consist of multiple layers on land, at sea, and in space, including space-based sensors and interceptor systems. But because the defense against long-range ballistic missiles remains the most controversial part of the initiative, it is the central focus of this analysis.

Washington regards short- and medium-range ballistic missiles (SRBMs and MRBMs) as tactical weapons in regional conflicts because they are able to pose a threat to the forces or allies of the US but not to US territory itself. Only intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) with ranges of several thousand kilometers are considered a strategic threat to US territory.

All ballistic missiles pass through three phases of flight. In the boost phase, which is over in just three to four minutes, a rocket lifts the missile into space. In the midcourse phase, which lasts around 20 minutes, the warheads travel along a ballistic trajectory under the sole influence of gravity. In the terminal phase, the warheads, having separated from the missile, re-enter the atmosphere and typically reach their targets in less than a minute. Defending against long-range ballistic missiles is extremely difficult in all three phases of flight.

Defense systems use different approaches to neutralize weapons in each flight phase. In the very short terminal phase, a warhead can be stopped only by interceptor systems that are stationed in the immediate vicinity of the target. This approach can protect key sites, such as military bases; however, an enormous number of systems would be required to defend a large country like the United States using this particular approach. For this reason, the technological focus has long been on the midcourse phase, in which more time is available to locate and engage the target.

Because of its fear of fueling global instability, the US government has in the past deliberately curbed the development of missile defense systems and relied primarily on deterrence to prevent strategic competitors from using long-range nuclear missiles. Over the past three decades, however, limited missile defense capabilities have been developed to respond to the threat posed by revisionist, isolated, and destabilizing states – North Korea at present and possibly Iran in the future. This course of action has been based on the assumption that such actors cannot be deterred by the threat of retaliation, which is why the United States must be able to fend off attacks.

The currently deployed Ground-based Midcourse Defense (GMD) system, which is intended to intercept missiles in the crucial, second phase of flight, was designed precisely for such threats. But even though the US system focuses primarily on defending against North Korean ICBMs, its effectiveness remains doubtful. In addition, breakthroughs in the development of such midcourse defenses are unlikely in the short term. For this reason, US officials concede that investments in and the expansion of the current system will not be sufficient to intercept Russian or Chinese missiles.

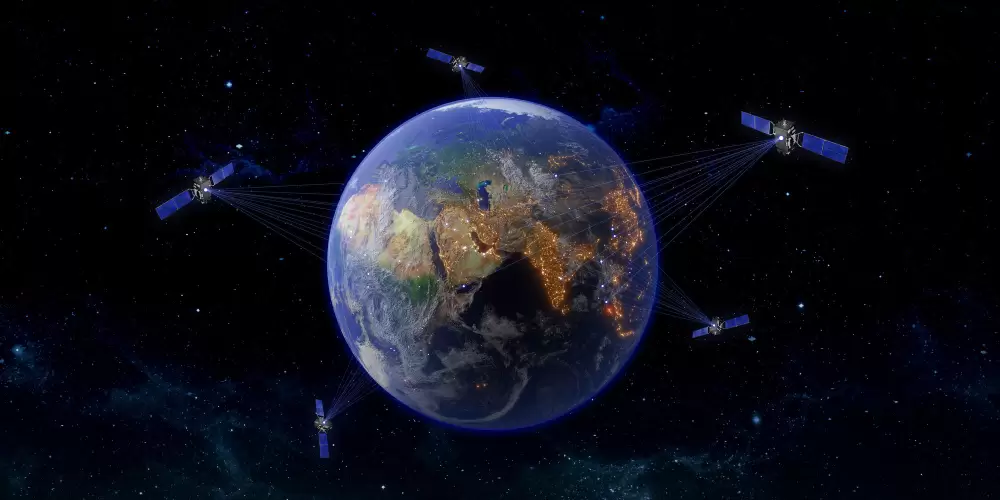

There are decisive advantages to intercepting missiles during the boost phase. It is in this phase that the missile is most vulnerable since countermeasures – such as multiple maneuverable warheads, decoys, and electronic jammers – typically come into play only during the midcourse phase. But because the boost phase lasts just three to four minutes, there is extreme time pressure. This means that ground-based interceptors would have to be positioned very close to the launch site – something that is not possible in the case of covering large countries like Russia and China or the world’s oceans. In theory, the problem could be solved with interceptor missiles in low Earth orbit (about 2,000 kilometers from the launch site). However, space-based interceptors would not remain stationary over a target but would circle in orbit; therefore, large satellite constellations – some for launch detection, others to carry kinetic or non-kinetic (e.g., laser) interceptor weapons – would be required to ensure seamless coverage.

This is where the main focus of missile defense within the Golden Dome initiative is to be found. Independent experts argue that for successful deployment, major advances in sensor coverage, battle management, and interceptor reliability are necessary, not to mention unprecedented investments in infrastructure. For its part, the US government claims that most of the required technologies already exist but warns that realizing the necessary “system of systems” will be challenging. The expertise of different agencies and the armed forces will need to be pooled, silo thinking overcome, and an integrated architecture created, US officials argue.

About the Authors:

Dr. Liviu Horovitz is a researcher at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs at SWP in Berlin, where he specializes in international security, nuclear deterrence, and arms control.

Juliana Süß is a researcher at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs at SWP in Berlin, where she specializes in space security, space governance, and the geopolitical implications of space warfare.