In response to the Eurozone crisis, a European Council ‘Task Force’ was established in 2010 to help strengthen EU economic governance. But which actors were most successful at shaping Task Force negotiations? Drawing on new research, David Moloney and Richard Whitaker show that member states that took up positions close to those of the European Central Bank tended to enjoy greater bargaining success. They also show how creditor countries were more successful than debtors in negotiations on the issues that mattered most to the member states.

To what extent are the member states, European Commission and European Central Bank (ECB) successful in achieving their preferred outcomes in negotiations on EU economic governance? While we already know quite a lot about this under standard EU decision-making rules, the influence of the ECB in informal forums such as the European Council’s Task Force on strengthening economic governance has received less attention.

The Task Force was established in 2010 to make suggestions for legislative changes to the EU’s economic governance framework to avoid a recurrence of the sovereign debt crisis that began in the Eurozone in 2009. It proposed tightening fiscal discipline, strengthening surveillance of member states’ economies, and ensuring better analysis and forecasts of states’ economic situations. These recommendations formed the basis of the EU’s so-called Six Pack legislative package.

In a new study, we find that being close to the ECB’s positions in the Task Force negotiations was associated with more success for member states. Our research shows that creditor member states were more successful than those with deficits. The findings suggest the ECB may be more influential when decisions are made outside of the formal legislative procedures and when the subject of negotiations is highly technical.

Negotiating positions and success

To establish member states’ and EU institutions’ positions in these negotiations and to understand how much importance they attached to the six major issues on which there was disagreement, we conducted 54 interviews with key-informants from the member states, the Commission and ECB. Figure 1 shows the average position taken on issues in the negotiations by each member state, the Commission and ECB. Positions were measured on a 0-100 scale where higher values indicate more fiscally conservative preferences such as favouring tighter fiscal discipline.

Figure 1: Mean position of each actor across the Task Force issues

Abbreviations: AT: Austria; BE: Belgium; BG: Bulgaria; COM: European Commission; CY: Cyprus; CZ: Czech Republic; DE: Germany; DK: Denmark; ECB: European Central Bank; EE: Estonia; EL: Greece; ES: Spain; FI: Finland; FR: France; HU: Hungary; IE: Ireland; IT: Italy; LT: Lithuania; LU: Luxembourg; LV: Latvia; MT: Malta; NL: The Netherlands; PL: Poland; PT: Portugal; RO: Romania; SE: Sweden; SI: Slovenia; SK: Slovakia; UK: United Kingdom.

As we would expect, Figure 1 shows an alignment based partly on creditor and debtor status. The positions of many of the debtor states (such as France, Greece, Spain, Ireland, and Italy) indicate opposition to fiscal discipline (with lower scores). Countries with current account surpluses in 2010 are among those taking the opposite view, including Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Finland, and Germany. The ECB also appears to have taken fiscally hawkish positions but the Commission less so.

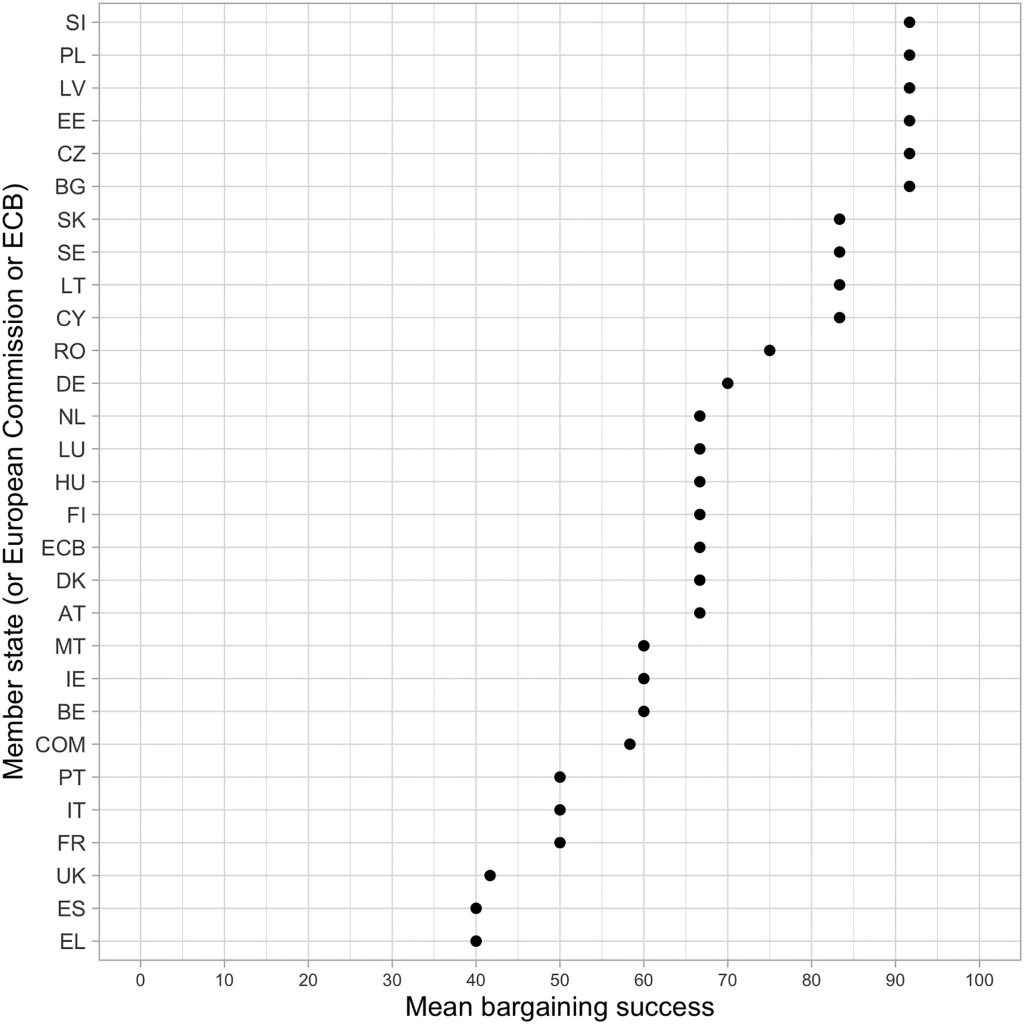

Figure 2 shows how successful member states, the ECB, and Commission were in the negotiations. Success is measured as the distance between each actor’s preferences and the final outcome.

Figure 2: Mean bargaining success of the ECB, Commission, and member states in the Task Force

Abbreviations: AT: Austria; BE: Belgium; BG: Bulgaria; COM: European Commission; CY: Cyprus; CZ: Czech Republic; DE: Germany; DK: Denmark; ECB: European Central Bank; EE: Estonia; EL: Greece; ES: Spain; FI: Finland; FR: France; HU: Hungary; IE: Ireland; IT: Italy; LT: Lithuania; LU: Luxembourg; LV: Latvia; MT: Malta; NL: The Netherlands; PL: Poland; PT: Portugal; RO: Romania; SE: Sweden; SI: Slovenia; SK: Slovakia; UK: United Kingdom.

Figure 2 shows the ECB was more successful than the Commission, on average, and provides mixed evidence of a creditor-versus-debtor alignment. Some states with current account deficits are among those with the lowest success (Greece, Spain, France, Italy, and Portugal), while some creditors (Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Germany, and Finland) performed better. Slovakia and Cyprus are outliers: both had deficits in 2010 but took positions towards the fiscal-discipline end of the scale (Figure 1) and were comparatively successful in the negotiations (Figure 2).

We next worked out how far being close to the ECB or the Commission affected bargaining success when we take into account other factors that might affect outcomes, such as GDP, population size and the salience of the issues at stake. We found that being close to the ECB was associated with more success and that the opposite was the case for proximity to the Commission.

The less formalised environment of the Task Force seems to have given the ECB a greater opportunity to influence outcomes than under standard decision-making procedures. On this basis, member states were likely to rely to some degree on the ECB’s expertise as part of deciding what position to take on each issue in the negotiations. Creditor member states were also more successful on issues that were most salient to those involved in the negotiations.

What does this tell us about the role of the ECB?

In reforming the EU’s economic governance framework at the start of the crisis, the ECB had several advantages. It had technical expertise that could only be rivalled by the largest member states. Its reputation among northern Eurozone member states was enhanced as a result of its response to the financial crisis, whereas the Commission had been tainted by its failure to fully implement the Eurozone’s rules for maintaining macroeconomic stability (the Stability and Growth Pact).

The ECB also has a far narrower mandate than the Commission. Thus, the Commission had to consider the positions of fiscal hawks and fiscal doves if it hoped to secure swift agreement for its forthcoming proposals in the Economic and Financial Affairs Council. Conversely, the ECB was in a much freer position to adopt a more hawkish line.

These ECB advantages in the Task Force have important implications given the Commission’s forthcoming proposals to reform the Stability and Growth Pact, which are even more urgent amid the financial implications of the invasion of Ukraine. If the ECB and a hawkish group of member states, such as the Frugal Four (Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden) prevail in the upcoming reforms to the Stability and Growth Pact, there may be little extra flexibility for member states struggling with their budgets.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in European Union Politics

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Union